Moke Avant-garde – by David A.M. Goldberg

Militia was reviewed today by David A.M. Goldberg, noted special contributor to the Honolulu Star Advertiser. His critical take on the Hawaii art scene is razor sharp and Keith was stoked he chose to check his work out. Read below…or link to the Star-Advertiser directly (note: article titled Image Scrimmage).

Moke Avant-garde

A Hawaii island artist’s cultural works carve out an insurgent’s point of view

By David A.M. Goldberg / Special to the Star-Advertiser

I’ve seen monster trucks with lava-grinding treads flying upside down royal flags, and ornate old English lettering in cut vinyl cursing me from rear windows. Kids rock T-shirts with King Kamehameha masked like a Mexican bandit, his image surrounded by a bristling ring of shark’s teeth. Threatening-looking dudes wear gear that reads “aloha” and “hi” in friendly noodle script.

In his first solo show, the inaugural exhibit at the newly opened SPF Projects, Hawaii island artist Keith Tallett’s “Militia” mixes this language of raw, often stereotyped, popular visual culture with his personal practices of surfboard design, tattooing and critical reflection on contemporary Hawaii.

He doesn’t paint portraits of Diamond Head, utopian scenes of underwater life or waves breaking perfectly under a full moon. Tallett borrows from modernist art strategies such as minimalism and abstract expressionism to boil down his Hawaii to a vocabulary of camouflage and tire treads, silhouettes of 40-ounce beer bottles, freight palettes, floral portraiture, calligraphy and color schemes rooted in surfing and auto culture.

“Militia” is an effort in consciousness-raising that begins with the viewer recognizing his transformations of local visual expressions. Many people will immediately recognize the macho codes of hunting, beach life, cruising, drinking and vehicle worship. They will also appreciate his take on photographing fruit and flowers that have come to represent Hawaii. Tallett leaves none of these objects or themes to themselves, instead cross-pollinating them through processes of addition, removal and juxtaposition.

His “Flying Hawaiian” series of plywood paintings coated in epoxy resin feature island essences of camouflage, tire treads, bullet holes and airbrushed color gradients, packaged in the thick gloss of high-end surfboards a la 1960s Los Angeles modernism. The treads clearly riff on flower lei, Polynesian tattoo patterns, the edges of traditional weaponry and tiki carvings. The vertical color fields behind them evoke the saturation of sunsets and the gloom of jungle twilight.

By simply raising them on wood blocks and leaning them against the wall, the artist warns the viewer not to treat these richly informative surfaces as paintings with a capital “P.” Tallet sees them as entities, spirits with personality and also, simply, as mirrors.

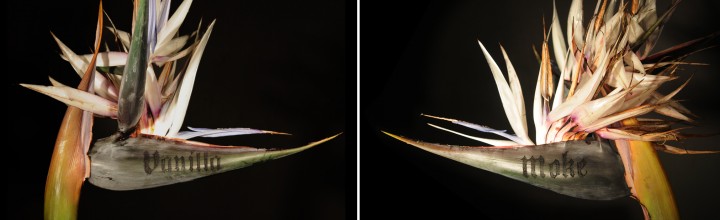

Or consider a pair of bird of paradise blooms, slightly battered as if pulled from the wild instead of a nursery. With their beaks aggressively facing each other, the backs of their heads split with chaotic clusters of white blooms, the two flowers look ready to fight, or like they just finished a round.Tallett has tattooed “vanilla” onto the cheek of the left flower, and “moke” onto the other — “vanilla moke” refers to a Caucasian moke — using real ink and an electric needle. Clearly, these “white boys” are ready to scrap. Near them, a “white lady” flower is marked with the word “noakup.” Get it?

This photographic series also includes ginger buds, antherium blossoms and other popular flowers tattooed with local concepts-in-one-word like “puinsai,” “ainoskedu,” and “tita.” Taking the flesh of these flowers as seriously as any of his human clients, he inscribes each with a personality derived from pidgin English. Bunches of bananas, similarly tattooed with local slang, also hang from the gallery ceiling as “live” versions of the photographs.

This kind of “code-switching” and “remixing” is a popular strategy in contemporary commercial design and art, but it can fail if there is nothing of significance behind the effort or in the material itself. The second amendment of the U.S. Constitution reads: “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.” By definition, a militia is not “regular army,” but a defense force raised from the civilian population.

Tallett reminds us that only the acts of surfing, hunting and tattooing are indigenous to Hawaii; everything else — from the flowers to resin to malt liquor to the English language — is invasive.

Though “Militia” is not a literal call to arms, it could be a first strike in an insurgency. From the perspective of this attentive outsider, there is no more volatile conceptual mixture produced when these words are spread like butter over a crust of Hawaiian self-determination issues that still glows red-hot.